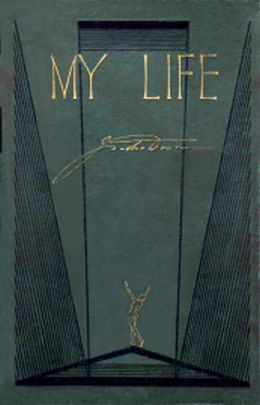

Joel’s lengthy note followed by Isadora Duncan’s autobiography: Isadora Duncan entered my life in the late 1990s. This was a period of significant change. I lost the ability to run; then walk, as a result of spinal damage caused by radiation treatment that cured me of cancer. Meanwhile, my physicians were deciding on a form […]

Archives for August 2014

September 2014 Motto

If I could tell you what it meant, there would be no point dancing it. — Isadora Duncan

Truly good news: Out of the jaws of death AGAIN, plus Gloria Steinem and Feminism

Truly good news concluding this season’s cancer scare. Dislike of purple prose such as “out of the jaws of death.” How Gloria Steinem, the feminist movement, and bra burning entered Dr. Imran Siddiqui’s operation room at the basement of Geisinger’ s Grey’s Woods facility, Greater State College, PA. What’s next? Truly good news explained. Summary: […]

“If anybody is lost, please raise their hand.”

Kris Kristoferson The story of how Kris Kristofferson came to write this song. With Willie Nelson and other notables, they sing the first stanza. Complete version with lyrics

August 2014 Motto

Cautious, careful people, always casting about to preserve their reputation and social standing, never can bring about a reform. Those who are really in earnest must be willing to be anything or nothing in the world’s estimation, and publicly and privately, in season and out, avow their sympathy with despised and persecuted ideas and their […]

Home following surgery

Dr. Imran Sidddiqui successfully removed my small tumor in his large operating theater surrounded by four nurses. The pain was minimal after the local was administered. Getting pain relief sometimes seemed more painful that the reflief. Finally, he poured so much into me that I will be numb until next Tuesday. It took ten minutes […]