Good morning. 4:52. Glenn Gould. Johann Sebastian Bach. Goldberg Variations. 1955. ++++ 5:46. Etta James. It’s a Man’s World. ++++ Good afternoon. 5:24. Carole King, Celine Dion, Shania Twain and Gloria Estefan. You’ve Got A Friend. ++++ Good evening. 6:04. Allentown. Billy Joel. ++++ 8:20. Barry McGuire. Eve of Destruction. ++++

Archives for November 2016

Tuesday Edition, My Music, November 29, 2016

Good morning. 6:47. Pablo Casals. Bach Suite Number 1. ++++ 7:38. Kacey Musgraves – Follow Your Arrow . ++++ 10:01. Jerusalem of Gold (Yerushalayim shel Zahav). Ofra Haza. [English Lyrics.] ++++ Good afternoon. 4:14. Glenn Gould. Mozart Sonata Number 11 ++++ 4:51. Bob Marley. Stir it Up. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n6U-TGahwvs ++++ 5:13. Marlene Dietrich. […]

Monday Edition My Music; November 28, 2016

Good morning. 6:34. W.A.Mozart Horn Concerto Nr.3 KV.447 ++++ 7:04. U2. Every breaking wave. ++++ “Every breaking wave on the shore Tells the next one there’ll be one more And every gambler knows that to lose Is what you’re really there for/” ++++ N.B. : “[E]every gambler knows that to lose Is what you’re […]

My Music Today Sunday November 27, 2016

Good morning 4:00 A.M. Beethoven sonata ++++ 4:45. I miss New Orleans ++++ 5:35. Stevie Nicks sings Landslide. ++++ “Oh, mirror in the sky What is love? “Can the child within my heart rise above? Can I sail through the changing ocean tides? Can I handle the seasons of my life?” vc ++++ 7:00. Dixie […]

Writing about food policy again (Why bother is a good question?): My published articles for Newsday are a good place to prepare for Donald Trump’s Secretary of Agriculture

Note: This is a work in progress. It contains too many typographical errors as I work my way to coherence. Please be patient until it is ready for the moral equivalent of prime time. Motivation: Last month I celebrated my 69th birthday in the hospital. This is the second year in a row I celebrated […]

Mozart’s last unfinished work was a requiem: He believed he was writing the prayer for his own death

“The Requiem Mass in D minor (K. 626) by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was composed in Vienna in 1791 and left unfinished at the composer’s death on December 5.” –Wikipedia ++++ Nine minute excerpt: ++++

Review: Politics of Food from The Natural Resources Journal (NRJ) at the University of New Mexico School of Law

At one AM (apparently in search of lost praise), I found the best book review I ever received. I first signed a book contract with New Republic Books in 1975 promising to deliver in less than a year. It was to be my first published book–as it turned out it was my third. My agent […]

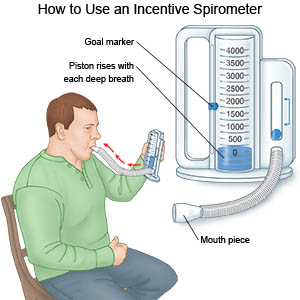

Billy Joel helps me recover from surgery

My lungs are clogged. After surgery at Mount Nittany Medical Center, the hospital commissioned a van to take me and my mobility device (a.k.a. scooter–an Amigo [accept no substitutes]) from State College to Pleasant Gap. There on my 69th birthday the HealthSouth Physical Rehabilitation nurse tried again to get me to breathe deeply–handing me the […]